Everything To Know About The Bell X-1 'Glamorous Glennis' Jet

When it comes to the latest and greatest in airplane tech, perhaps no other organization is better at developing these cutting-edge aircraft than the Armstrong Flight Research Center, HQ for NASA's X-Plane program. Home to many of the weirdest aircraft designs ever conceived, the X-Plane program has pioneered many flight innovations.

Case in point, it's the birthplace of one of the most groundbreaking and innovative planes ever developed, the Bell X-1 (originally the XS-1), and continues to test and discover new innovations for commercial airline companies and military organizations to this day.

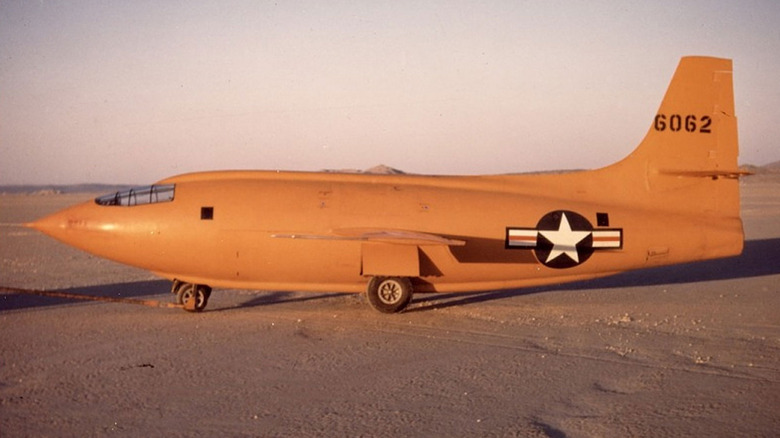

Bell Aircraft Corporation's X-1 Glamorous Glennis was the first aircraft capable of breaking the sound barrier, and served as an important aeronautic step for American engineers hoping to construct the next generation of jets. While many may be familiar with Charles "Chuck" Yeager's X-1 flight — the first time a pilot achieved supersonic flight — the origins and history surrounding the development of the X-1 is also an interesting tale.

The Bell X-1 was the first supersonic jet ever

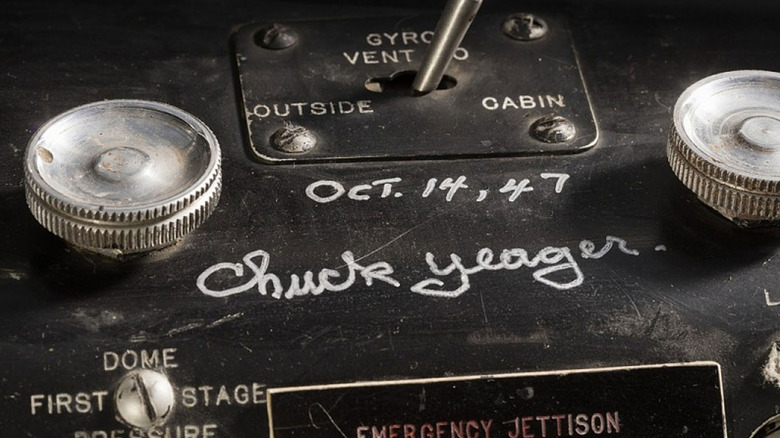

Flying high above the dusty Mojave Desert below him, Captain Charles "Chuck" Yeager of the United States Air Force (USAF) was the first person ever to fly faster than the speed of sound. Yeager's first supersonic flight would occur on October 14, 1947, and the Bell X-1-1 was the first aircraft in history capable of reaching supersonic speeds, achieving Mach 1.06, or 700 miles per hour, at an altitude of 43,000 feet.

Nicknamed Glamorous Glennis in tribute to Yeager's wife — the famous American actress Glennis Dickhouse — the Bell X-1 was a culmination of years of research and development by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the U.S. Air Force, and the Bell Aircraft Corporation.

Air-launched from a Boeing B-29, the X-1 utilized a rocket-propelled engine to reach its blistering speeds. The Bell X-1 Glamorous Glennis would go on to inspire modern fighter jet design and serve as an important precedent of an aircraft being manufactured for purely research purposes, without military or commercial intentions.

The Bell X-1 solved an aerodynamic problem for engineers

Though the first supersonic flight for the X-1 would occur in 1947, the onus to develop an aircraft with its capabilities began all the way back in the late 1930s. Aircraft engineers at the time were experiencing adverse effects of subsonic and supersonic airflow over airplane wings, which caused increased drag, severe turbulence, and a loss of control.

To find a solution, John Stack, Erza Kitchener of the Army Air Forces (later the USAF), and Walter Diehl of the Navy set out to create an organization that was capable of performing specialized aircraft research to obtain more supersonic aeronautical data. That idea would spur the creation of the NACA Muroc Flight Test Unit, which would later become the Armstrong Flight Research Center.

In addition to utilizing data collected from tests on the Bell X-1, the X designation and the program tied to it would go on to spur over 75 years of aeronautic research, which is helmed by NASA scientists today. The data and testing done by the X-1 gave engineers the information they needed to overcome design problems associated with flying faster than the speed of sound. This would include information about stability and control, high-altitude flight, and wing and tail loading.

Leaders were skeptical of the X-1's hardware

Initially, Bell Aircraft was tasked with building three separate X-1 aircraft. The first two would be the X-1-1 and X-1-2, the latter of which would have a thicker, 10 percent thickness/chord ratio on its wings compared to the X-1-1, which would be designed and tested at eight percent thickness/chord ratio — thinner in comparison to the other fighter jet designs of the time.

A Reaction Motors, Inc. XLR-11 four-chambered rocket engine would power the supersonic plane. With 6,000 pounds of thrust, the engine burned liquid oxygen and a mixture of alcohol and water to propel the plane forward at supersonic speeds. The XS-1-1 and XS-1-2 did not use turbopumps to feed fuel to the rocket engine, instead employing direct nitrogen pressurization.

The fuselage of the craft was designed like a .50 caliber bullet and masked what was within: two propellant tanks, 12 nitrogen spheres for cabin pressurization, and 500 pounds of flight-test instruments to collect the critical data that the operation had set out to collect.

Chuck Yeager was not the first to fly the Bell X-1

Though Yeager is well-known as being the first pilot to fly faster than the speed of sound, he wasn't the first to test the Bell X-1. That would happen on Jan. 19, 1946, at Pinecastle Field in Florida by test pilot Jack Woolams.

Like the supersonic flight that would be made by Yeager a year later, the X-1-1 would be deployed from a B-29, with Woolams performing 10 glide flights to test the handling of the craft. In March, the X-1 would be returned to Bell so that the rocket engine could be attached and the plane could later be delivered to Muroc Field (later Edwards Air Force Base).

Later, at Edwards Air Force Base, in December of the same year, Chalmers "Slick" Goodlin would pilot the X-1-2, nearly surpassing the speed of sound, reaching Mach .79. He would just narrowly miss this accomplishment, with Yaeger taking the prize less than a year later.

Charles Yaeger would take his first glide flights with the X-1 at Edwards in early August, and by the end of the month, he reached speeds of Mach .85 before achieving greater than Mach 1 speeds on his historic flight. This was made possible by the slightly smaller wings of the X-1-1 over the X-1-2 model.

The X-1's legacy continues today

The X-1-3 would be the final iteration of the X-1 generation of Bell planes. This aircraft would use a turbopump and was geared to go Mach 2.4, or over twice the speed of sound. However, the final version of the storied plane would end in disaster when, on Nov. 9, 1951, while the X-1-3 and the B-50 carrying it were on the ground after a malfunction in the air, a dull thud was followed by a violent explosion emanating from the center of the X-1-3, destroying both aircraft. It would take a year for pilot Joseph Cannon to recover from the severe burns across his body.

This would mark the end of the first generation of X-1s, as developmental delays and the research and development for the next generation of planes, the X-1A, X-1B, and X-1D, were already underway by the USAF. Though it would mark the end of the project that helped humanity break the sound barrier, it wouldn't be the end of the X-Plane program or the Armstrong Flight Research Center's research.

Indeed, the Bell X-1 Glamorous Glennis would be just the first in a long series of experimental X-Planes that would discover and test new aeronautical innovations to this day, including the technology that enabled the manufacture of the controversial F-35 stealth fighter jet. Today, the X-59 Quesst is the latest NASA creation seeking to usher in another age of supersonic flight — free of a sonic boom — for commercial airliners.